BOK FEATURE: Mac’s role in 1995 win should not be underplayed

When the Springboks arrive in Auckland in September for what is being built up to as the international game of the 2025 rugby year, much will be made of the fact that the All Blacks haven’t lost there since France won there in 1994.

That is 31 long years since the French won with a last gasp try from a counter-attack that went all of 95 metres and was described by the France players as “the try from the end of the world”. However, while it is true that New Zealand has not lost in that time at their most formidable home fortress, which is a phenomenal record, they haven’t played all their games there without blemish.

The British and Irish Lions drew 15-all with the All Blacks at Eden Park in the 2017 series, and there was another draw - 18-all against the Boks in the third test of the 1994 series.

That was the next game to be played in Auckland after the loss to France, and had the denizens of South African rugby known then that the team had achieved a stalemate at a venue where the Kiwis would go unbeaten for more than three decades, and still counting, they might not have done what was done next - axe the coach, Ian McIntosh.

The Boks score two tries to nil in that game, with All Black fullback Shane Howarth responsible for all of his team’s points. It really wasn’t a game that the Boks, captained by Francois Pienaar, should have lost.

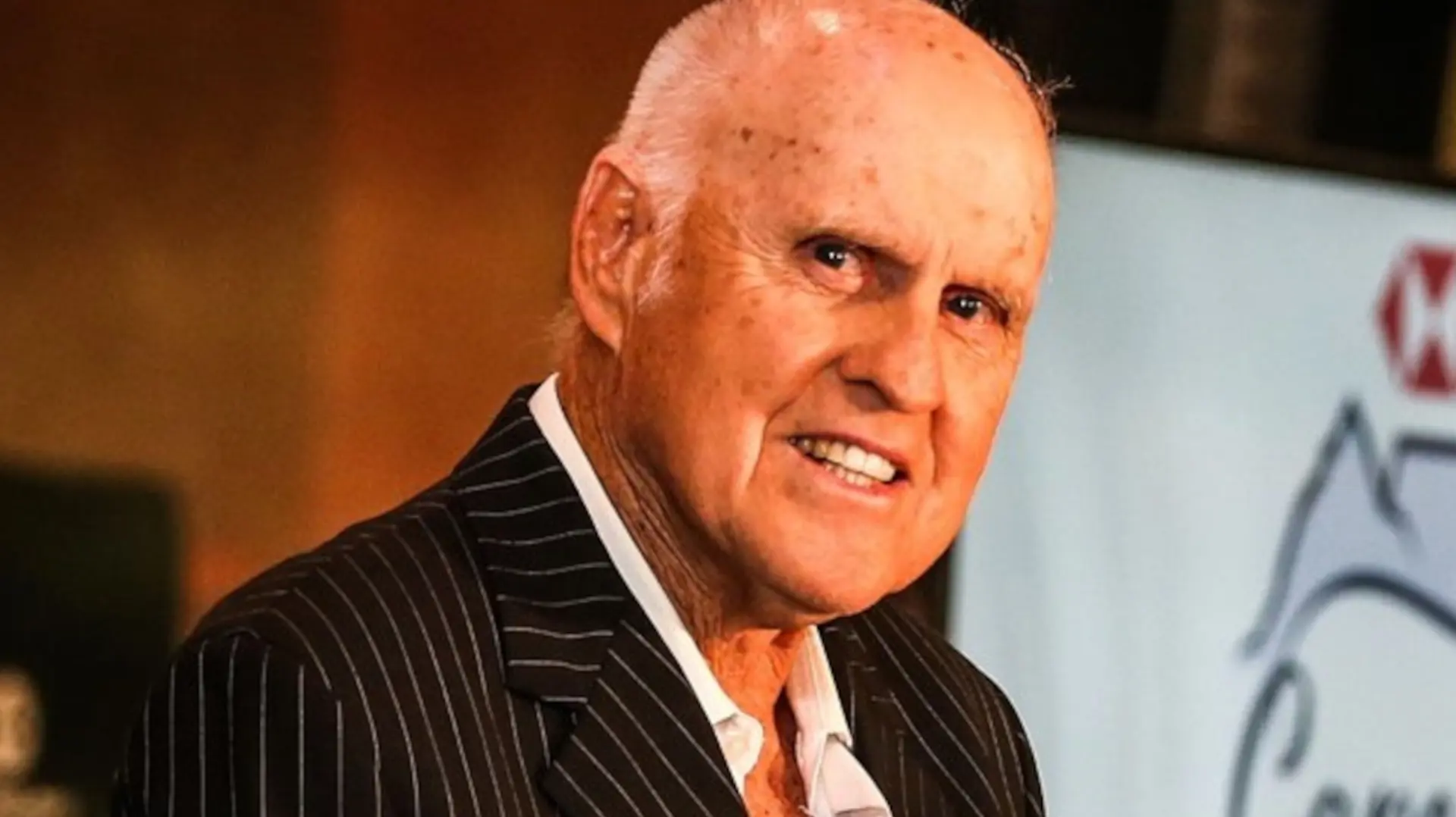

The abiding memory of that game for those of us who were there covering it from the press box though might not have been of Howarth’s equalising sixth penalty 10 minutes from time, but something said by the legendary former All Black lock Colin Meads at the post-match press conference.

Meads was the All Black manager in that series and it was in that capacity that he was in the press conference room before the arrival of the two coaches, New Zealand’s Laurie Mains and McIntosh.

“So,” he asked us, “you guys are all very clever rugby people, can you tell me why one team scored two tries to nil today but it was a draw?”

INDISCIPLINE AND A SELECTION MISTAKE

From memory, there was no answer to Meads’ question, just several dumbfounded looks. Turn back the clock though and I might now forward an answer - the one team was more disciplined. It was in fact a howler from the Boks that gave away the penalty that drew the game.

And it was thus for most of a closely fought series, with the Boks’ indiscipline costing them in the first test in Dunedin, when Tiaan Strauss was the stand-in skipper, the poor goalkicking also not helping and leading to the controversial omission of the excellent Bok fullback Andre Joubert for the second game of the rubber in Wellington.

That selection didn’t endure McIntosh, known as Mac to all and sundry, to some of the players, particularly not to the feisty but intensely loyal wing James Small, who was in tears when he went to the coach and told him exactly what he thought.

McIntosh, who passed last year, readily acknowledged that as a mistake in later life, but he wasn’t the sole selector. In fact, he was on tour with a squad that had been chosen by seven selectors, which was why he travelled without future World Cup winner Joel Stransky.

Back then there was a hoary old line pedalled ad-nauseam by hacks who had written about the Boks in the pre-isolation era that “New Zealand is the graveyard of Springbok coaches”. Which was true if you looked back at previous series losses dating from 1956 through to 1981.

So when the Boks lost the series McIntosh’s axing appeared fait accompli, and it was more the hoo-ha around the future of manager Jannie Engelbrecht that created waves when the Boks arrived home. The statesmanlike Morne du Plessis, a Bok captain from an earlier era, probably summed up the attitude when he said in an interview: “Mr McIntosh knows how these things work”.

Meaning that Mac wasn’t a winning coach, so his position was in jeopardy. And history reflects that Kitch Christie took over from there, brought in fitness and discipline as the main tenets of his philosophy, and a team made up mostly of players who had first been selected by McIntosh won their way into South African folklore by winning the 1995 Rugby World Cup.

LAID THE FOUNDATION

The 30th anniversary of that achievement is being celebrated this week, with the role played by the former South African president Nelson Mandela, the father of the South African nation as it is today, something that inspired more than one book and a Hollywood movie, still making it the stand-out World Cup win.

“They (that team) laid the foundation for future World Cup successes back in 1995 and they wore the jersey with pride and respect,” said current Bok wing and two-time World Cup winner Cheslin Kolbe when asked this week about the impact of 1995.

Kolbe was still too young to take it all in back then, but he’s seen videos and the legacy that was set. Skipper Pienaar and his team, plus the coach Christie, who came in saying he was going to do “an ambulance job”, and he did, were installed as national heroes.

However, with the benefit of the perspective you can gain from a long view back at history, it would be remiss not to recognise McIntosh’s role in making the Boks the competitive force they were at that World Cup, from getting them back on track after a disastrous readmission to international rugby after years of isolation in 1992.

WILLIAMS WAS ALWAYS DOOMED TO FAIL

All of the first three Bok coaches of the post-isolation era have now passed on (Gerrie Sonnekus was a fourth coach but never got to actually coach the team). Professor John Williams was the first, and he was doomed to fail if you recognise the hurdles he had to overcome.

For those who don’t know, Williams, as he told me in a book, The Poisoned Chalice, I wrote about the Bok coaches, was appointed in the most unprofessional manner (which was maybe okay because rugby was officially still amateur back then).

“I started to get phone calls from people in around April 1992 saying they believed I had been appointed as Springbok coach,” recalled Williams in an interview conducted on his game farm near Alldays on the Botswana border in 2013.

“I told them that it couldn’t be true. Surely there would have been a letter of appointment? At the very least I would have received a phone call from Sarfu. But I had nothing of the sort, so I assumed it was all just rumour.” But as the year progressed the “rumours” intensified, to a point where Williams decided he had to find out.

“I phoned Johan Claassen, who was on the Sarfu executive. I asked him if it was true that I was Springbok coach. Johan said that as far as he knew, I had been appointed at an earlier executive meeting. This was at the end of May and the Boks were due to play at the end of August. If we were going to play two tough matches (against the All Blacks and the world champions Australia) I needed to get cracking with preparations.”

Williams then related how he had phoned Arrie Oberholzer, then the general manager of Sarfu, who also confirmed Williams’ appointment in addition to informing him that he would not be able to work with the players until a few days before the test against the All Blacks because “Doc Luyt (Transvaal president and Sarfu vice at the time) has a Currie Cup to win”.

Those were the days of provincialism, and South African rugby, starved of international rugby for so long and duped into believing the Currie Cup was a quasi-World Cup, was also incredibly arrogant at that time. Choosing New Zealand and Australia as the first opponents after so many years of isolation confirmed that.

South African rugby was behind the eight-ball, as quickly became apparent, and Williams, who hadn’t coached since being in charge of Northern Transvaal (the Bulls) in 1989, was understandably underprepared.

He was also given a management team rather than choosing one, and like with McIntosh who followed him, he had to work with many selectors.

SA’s FIRST NON-BOK NATIONAL COACH

It wasn’t surprising that Williams didn’t see out the year, and after Sonnekus was appointed and then fell out because of a controversy he had been embroiled in at his union, Free State, Sarfu had little choice but to do what they’d never done before - appoint a non-Springbok as the national coach.

And so it was that McIntosh, a Zimbabwean by birth but who had coached Natal to two Currie Cup titles in three years, including that province’s first ever trophy in 1990, came to be the second Bok post-isolation coach. He was admired in his home province but treated with distrust outside of Natal, where his revolutionary playing style, dubbed “direct rugby”, wasn’t understood.

Direct rugby was played by every international team not long after that, but McIntosh was seen as an outlier in his home country, where innovation in those days was often treated with mistrust, and he was criticised mercilessly every time the Boks lost under him.

Which they did, but there is context - I happened to give Mac a lift to his car after bumping into him on the outerfields of Kings Park following his first test, a draw against France, and he told me then that the players hadn’t followed his game-plan.

Hennie le Roux was then the game-driver at flyhalf and it is understandable that he may have been reluctant to embrace something new as the Transvaal team he was part of was playing a very different way. It may not have been a coincidence that when the Boks won their first game under Mac, against the champion Australian team in Australia, he had Natal players who understood his plan, Robert du Preez and Stransky, as his halfbacks.

But when the Aussies fought back to win the series, with the sending off of James Small for backchat in the second test a series turner, McIntosh was predictably blamed for playing “stock car rugby”, with ex-players and critics not understanding why the inside centre (usually another Natal player, Pieter Muller) was taking the ball up to the gainline and taking contact and generally operating as an auxiliary flanker.

CLAMOUR FOR HIS HEAD STARTED AFTER AUSTRALIA

The clamour for his head started then, with his critics completely overlooking the fact that the Boks had been highly competitive in a series against the world champions in Australia and had only lost the series by a narrow margin.

When the likes of Henry Honiball, tailored for McIntosh’s game, started to come through and McIntosh ended his first year well with a series win in Argentina, it looked like his coaching career with the Boks was up and running.

But alas, Honiball was injured at the start of the following year and was unavailable for the trip to New Zealand. And McIntosh’s fellow selectors out-voted him when it came to Stransky, who Mac knew would have been good in the New Zealand conditions.

The only real big blowout of the Mcintosh era was the comprehensive loss to England at Loftus in the first test of a two game series before the New Zealand tour, but again there was context - the team only gathered a few days before the game. Sure enough, with another week to work with the team, they bounced back to thrash England 27-9 at Newlands.

With Le Roux at flyhalf Mac struggled to get his game plan through, but during the New Zealand series there were signs that the penny was starting to drop. After the Eden Park test I ended up having a drink with McIntosh to clear the air over some of the things I had written, and he told me then that Le Roux was starting to understand his game and starting to implement it.

MAC’S GAME PERFECTED UNDER KITCH AT SWANSEA

Unfortunately McIntosh never got the chance to see his game grow further as a coach, but he was at Swansea as a spectator a few months later to see the Boks thrash a very good Swansea team under Christie’s coaching, a result that stunned the UK rugby media as the Bok opponents were highly revered at that time.

“That was the day I saw the Boks finally perfect my game,” said McIntosh.

And Brendan Venter, who later went on to become an astute and highly regarded coach and played under both McIntosh and Christie agreed with that assessment. Venter told me that while Christie made changes to the discipline and got the players incredibly fit, he never considered Christie much of a tactician and that the Mcintosh game plan was continued under the new coach.

“To me, Kitch was not a tactician and the fact that he went on to win the World Cup may be an indication that sometimes it doesn’t matter how strong you are tactically when it comes to whether or not you are a good coach,” said Venter in The Poisoned Chalice.

“Kitch succeeded at the Boks by surrounding himself with people who he believed in and who believed in him. He picked 13 Transvaal players, and then even called up the Transvaal B hooker when other players fell out.

"The plan to win the World Cup was purely and simply that there was a low road and a high road, and that we must take the high road by beating Australia. That doesn’t qualify as a tactic… It was all about fitness and discipline.”

Venter added that McIntosh had a plan and that the influence of his coaching came out on the field during the World Cup. Others, such as Mark Andrews, who played for Mcintosh at Natal, have echoed those words.

That is not to denigrate Christie. He was the right man at the right time for the Boks, and maybe they did need a kick in the pants when it came to discipline.

Speak to the players in that team and they will also tell you that Ray Mordt’s never ending fitness sessions at the Wanderers in the months before the World Cup gave them confidence that they would win when the final went to extra time, with Stransky’s drop-goal the eventual clincher.

But McIntosh, in the years preceding that, set the Boks on the path they followed in terms of their game, and while at the time we did not know it, close series defeats in Australia and New Zealand, when compared to what was to come in those countries in the Tri-Nations era that followed, weren’t the disasters they were made out to be.

Particularly not so soon after South Africa’s international comeback and in an era where a Bok coach could be appointed to the job and not be told that he had been.

Advertisement